To Read, or not to read – that is the question. I think of vital choices like Shakespeare’s poor Hamlet who uttered, “to be or not to be….” while he considered whether to live and suffer life’s slings or die and possibly be at peace. Hamlet was unsure about life after death, so it wasn’t a “black or white” choice for him, but we can be surer about the “not to read” choice. When it comes to education, insight, and exposure, the result of a vital choice about whether or not to read is “black or white.” It is reflected in our culture. The abundance of schlock choices is increasing in direct proportion to the substantive choices decreasing. How many people do not read anything at all?

Alas, if only I had one-zillionth Shakespeare’s brilliance at causing individuals to see themselves through the mirror of his complex characters! Of course, Shakespeare didn’t have to compete with TV, movies, or video games. As it is, the optic nerve and the auditory canals have often become the pickup route leading to the largest human garbage dump of all – the brain. Even if I could manage to dash off a few breathtaking lines, the kind of thing which, doubtless, would dazzle with the force of its impact if only it might penetrate the gray matter, there would still be the need to market it effectively enough to garner sufficient notice. Writers’ tools consist of the basics, just ink on paper. No exploding paint balls, whistling rockets, peephole activity, pulsating flashes of free-falling bodies, or dizzying camera angles. Not even any red blood or purplish green ooze. None of it. Just the power of language, the music of thought, the connection of ideas jumping synapses; not following trends blindly with trite buzzwords, but taking control of the thought process. A lot of how this is accomplished comes about through reading/thinking or thinking/reading, then acting. In the case of writers, reading opens thought and feeds creativity. Imagine no polls, no comparisons with neighbors, or no political correctness, but just brave logic. It would be as liberating as morphing an overpopulated rat colony into a bevy of butterflies.

Everyone wants to fly, to be free. Reading has a way of doing just that by unleashing minds and voices. It takes us over the world, back through time and forward into the future. It validates ones’s thoughts or offers new insights. Instead, too often we stare and distract at computer and phone screens, searching endlessly, lured by excess, failing in our quest to quench the thirst. We resist most the work that is hard, effort that is demanding of our minds and bodies. Reading teaches, comforts, compares, reveals, provokes, engages, inspires; it does all this while exercising and revealing the many layers of the mind.

Reading the stories of other lives and writing the stories from our own experiences forms a human link through ages of time. People say, “I don’t have time to read newspapers, books, or magazines. I get all the news from TV or my phone or computer.” It’s true that we are flooded with soundbites from over the globe. What seem like nanoseconds of information constantly bombard us and are shoved aside for even more breaking news so that our heads are reeling. There is too much repetition and too much selective sensationalism. Ignorance is directing intelligence. What to do?

Limit the noise. Decipher the competition for attention. Think for yourself. Assess the information. Do some research. Read history, read about cultures and places, read lives, loves, and outcomes of real people. Feed your own mind rather than allow the clamor to deceive, spew random opinions, and exert control. That familiar sequence in Act III, Scene I of Hamlet states it best: “Madness in great ones must not unwatched go.”

If we lose our love of reading and get caught up in the treadmill of speedy words going nowhere, we’ll lose what made great thinkers unique. There are so many books with treasures to unlock. They were freely given to future generations and exist long past their authors. The founding fathers of our country were readers and writers. Their thoughts became our basis. We can’t all write books, but each person can leave something written which expresses free thought and individual ideas. It can be a recipe, a poem, a hand-written letter or note. No time? Give up one phone call, one snack, one TV program, one Facebook scrolling session, and you’ve got it. It can mean the world to someone who will read it.

Read and write go together like fingers on the same hand. They have a direct line to the brain. To read or not to read is an individual decision, but I cannot imagine an existence without it. It turns my motor, is my barometer, connects me with humanity. It is a way to satisfy insatiable curiosity about everything. The summer between fifth and sixth grade found me diligently building a neighborhood newspaper where I wrote every feature article, opinion piece, and ad. There were interviews with all the neighbors, human interest stories about their pets, announcements about lost dogs, recipes generously provided by my grandmothers, garden tips from my mother, and much more. I clipped headline letters from our regular newspaper and glued them into place for my column titles and drawn illustrations. It was a daily labor of love that I hoped would help everyone love to read as much as I did. It was shared with those who seemed to enjoy reading about themselves and there was a lot of kind interest in my early journalism. The Secret Garden, Heidi, and Black Beauty were favorites among dozens of books which inspired my childhood attempts to create stories for others.

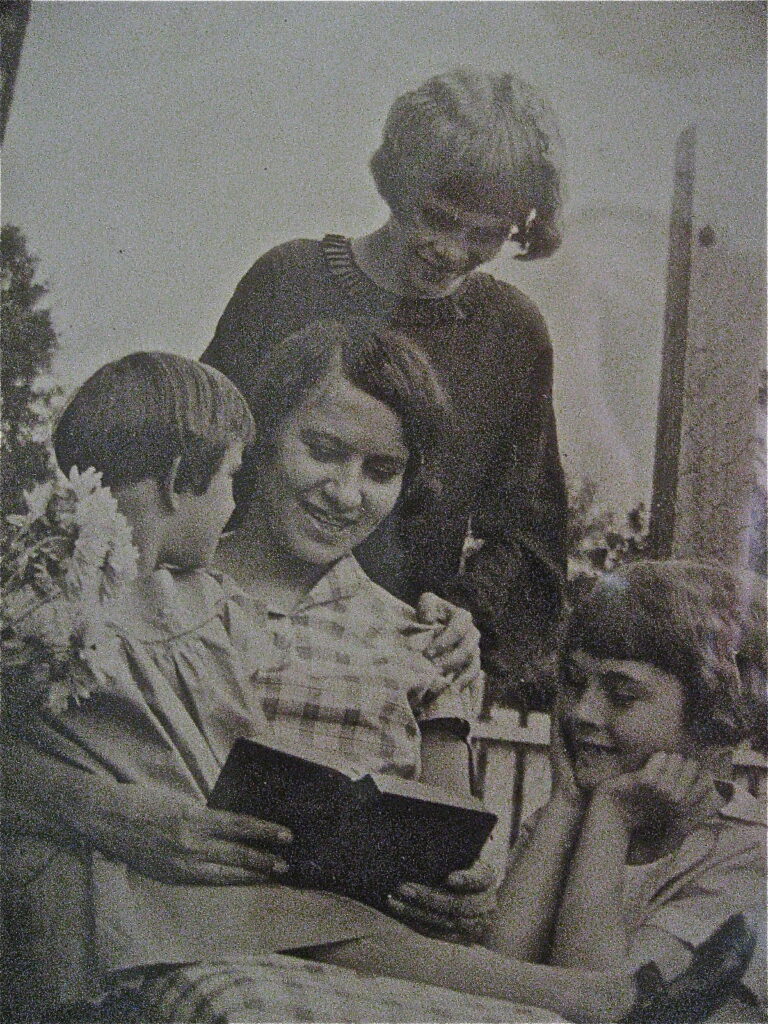

READ! Encourage your children to read and entertain themselves. Let them see you read. Laugh, cry, and talk together about stories. You never know where it will lead, but lead them, it will. Here’s my grandmother, Emmie, reading in 1928 to my mother in her lap, and my two aunts. This led to some very great things!